Nicholas Bowman-Scargill didn’t set out to build a monument to the past. When he revived Fears — his family’s historic British watch company — it was with the conviction that heritage should be a foundation, not a limitation. As the fourth managing director and great-great-great-grandson of the brand’s original founder, he has steered Fears into a new era defined by quiet sophistication and a vision that reaches decades into the future.

Under his leadership, Fears has developed a reputation for refined design that resists trends, earning respect for watches that feel both familiar and entirely contemporary. Yet what truly distinguishes Nicholas is his belief that a business can be commercially successful without sacrificing integrity. His ambition to create “good capitalism”, where long-term partnerships, fair treatment of suppliers, and genuine care for employees take priority, offers a refreshing contrast to the more extractive practices often found in luxury.

Instead of simply recreating archival pieces, Nicholas asks: “What would Fears look like today if it had never closed?” The answer has produced distinctive models like the Jump Hour and the Arnos, designs that speak to both the brand’s history and his ideals.

Personal Style & Brand Embodiment

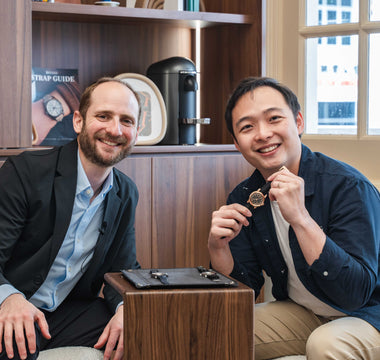

Ken: You strike me as the most well-spoken, well-mannered, well-dressed person. If I search "British sartorial gentleman" on ChatGPT, I feel like your face would appear. Is that just your upbringing?

Nicholas: That's very kind of you; I'll pass the kind words on to my tailor. My father's always had an eye for style — how to dress, how to put colours and textures together, casual and formal — so I grew up in this environment where putting on a suit was more than putting on a uniform. It was a way of expressing yourself. From a young age, I was fascinated with ties, pocket squares, and lots of jackets. We have to, as humans, put clothes on in the morning, so why not take a moment just to put care and thought into it? It brings so much enjoyment to the day.

Ken: I look at you and feel like you're the perfect embodiment and ambassador for your brand. When I think British, there's a certain stereotype, and you really represent the brand well. I can see that style and elegance through the watches you design and create.

Brand Revival Process

Ken: You revived Fears in 2016. What goes behind reviving a brand? Do you just buy the domain, get the Instagram handle and start?

Nicholas: People may have heard how I discovered Fears being in my family's history—I'm the great-great-great-grandson of the founder. From a practical standpoint of reviving a brand like Fears, when I first decided this might be something I want to do for real, I spoke to my parents. My father is a corporate lawyer, so he immediately gave practical advice. He said, "Don't tell anyone you're doing this. Tomorrow, I'll help you incorporate a company," which in the UK is very easy — costs 13 pounds, done within 20 minutes. "Also, we need to investigate buying the trademark. Does anyone own it already? Has it lapsed? If you don't own your trademark and the company, you own nothing."

From that, you realise what other things you need to own. Domain, Instagram handle, YouTube. Before you even think about what kind of watch, what kind of company Fears could become, you have to do that. Today, if I have an idea for a watch model name or a different service, the first thing I'll do is buy all the domains, trademark the names.

It's about the love of watches, but also ensuring you protect all the energy and effort you put into them.

Ken: That doesn't sound too different from starting a new brand. Is there anything additional because you're reviving an old name that you have to do or prove?

Nicholas: No, there isn't officially. Though anyone who's worked in a family business would appreciate this, I didn't have to get sign-off from the family, but it was respectful to talk to everyone and make sure they weren't planning to do the same thing. You come down the generations, it's a family tree that expands, and you realise there are all these branches of people who have Fears as their surname. So it's respectful to check with them and reassure them that I'm not just trying to take our family's legacy and cash in on it. I'm going to take it and be respectful to it, to grow it and revitalise it.

Vision & Business Philosophy

Ken: Let's talk about the vision for the brand. Where do you see Fears in the next 5, 10, 20 years?

Nicholas: Back in 2016, when I restarted, very unusually, in the business plan, I focused almost more on the 50-year vision — where do I want Fears to be in 50 years? When I speak to other business owners, I realise that's not how people think. People focus on the next five years. My business plan has the next 12 months, 5 years, 10 years, and then 50 years. But that 50-year plan is so important because in the last nine years, we had Brexit, the pandemic, wars and all kinds of unpredictability.

You have to find that balance of being flexible, able to adapt and change, but also not veer off course. I think of that little map on the screen in front of you on a plane. When you hit bad turbulence, you're going up or down 1,000 feet, maybe you make a detour, but the endpoint is still the endpoint. The same with a ship. As a company gets bigger, it becomes more like a ship and less like a plane because you've got to make plans further in advance.

The 50-year vision has never changed. And the 50-year vision for Fears actually has nothing to do with watches.

The 50-year vision is for Fears to embody the British essence of good capitalism.

Ken: Wow.

Nicholas: To embody something means to be the poster child for it. We're a British company. I'm very proud to be British, though I'm international in my outlook. For Great Britain to thrive, we have to work with people around the world. Good capitalism is about giving up maybe a couple of percentage points on margin to ensure you work with good suppliers who share your values. You ensure you pay people and help them grow with your growth. When I studied economics at university in the 2000s, running a successful business was all about profit and trampling on as many people as you could to get there. I don't think that's sustainable. To me, sustainability isn't just about the environment — it's also a moral responsibility. Take Fears as a poster child. That means it has to be a good company, well-known and well-respected.

Ken: That is one of the most inspiring vision statements I've heard. Even for us, our vision statement is tied to our product and brand. It isn't about values we try to bring or lofty ambitions beyond that. When you first said it's not about watches, I was prepared to hear you're going to do something else, but it's the ideals you're trying to move towards. Kudos!

Nicholas: That's the vision. But then it trickles down. Everyone in the company has as their laptop screen background four words in black on grey: the mission statement. "Building luxury with integrity." I always say to my colleagues, if you're ever in doubt on a decision, read those four words, and they will clearly tell you whether you should make that decision.

This builds into what I want Fears to become. When I was growing up, I loved watching classic Hollywood films — How to Marry a Millionaire, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. In that famous song, Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend, she lists brands like Cartier and Harry Winston. I would love it if someone were to do a remake one day, so that Fears would be one of the names listed. This classic old-school luxury with integrity to what it's doing; not flashy luxury. I always describe Fears' take on luxury — we whisper rather than shout.

Brand Identity & Customer Appeal

Ken: Let's talk about your brand and watches. What makes Fears special? Who are your customers? What makes them buy a Fears over a Tudor, Longines, Omega or Cartier?

Nicholas: This is something I ask myself because I need to understand it to gear the company toward our customer base. What we've done is try not to over-analyse it. We know who becomes a Fears owner, but it's so diverse — everything from hardcore watch collectors who know every detail right through to people who walk into our boutique wanting to buy their son or daughter a 21st birthday present.

I've always lived by that motto Henry Ford supposedly said — if he had asked his customers what they wanted, they would have said faster horses. It's not being arrogant, saying I know best, but having confidence.

As a luxury brand, you've got to have confidence because people are coming to you to be the expert. People are coming because you're good at what you're doing.

Our design philosophy comes down to our trademarked motto: "Elegantly understated since 1846." Elegance is a very British trait. Elegance doesn't shout, it whispers. It's something very difficult to pinpoint. If someone's elegant, when you ask how they're elegant, it's very difficult to say because of this or that. The understated part is that we over-engineer our watches. Some of the things I get most pleasure from when doing events are people holding the watch and saying, "I love the quality." That's interesting because it's very difficult to convey quality. Quality feels objective, but it's actually subjective. When you hold something you know has been well-made and carefully thought out, it feels good. That's what appeals to people over other brands, combined with how we sell, and how people are brought into the Fears family. It is old-school luxury, very respectful.

Ken: Looking at the pieces here, there's a certain charm you can't quite put a finger on. I've only been handling the watches for a few days, but there is that consistency, and what you described — you whisper luxury. That's such a reflection of you as a person.

Brunswick Jump Hour Discussion

Ken: I wanted to dive into the Brunswick Jump Hour. We just came from Watches and Wonders and saw so many jump hour models. You guys launched yours in January 2023. What makes jump hour so appealing?

Nicholas: If I'm being honest, it's kind of a weird way of telling time. Yet, it's actually very intuitive. You've got this mechanical hybrid of digital and analogue. At first, most people look at our Jump Hour, which has that large 5mm window at 12 o'clock, and assume it's a date. When you explain it's the hour, for people who aren't watching people, they fully get it straight away. They light up with excitement because time is told in two ways — two hands going around in a circle, or digital. When you have this combination of both, people get very excited. When they wear the watch, it takes a couple of hours to get used to it, but once you do, it's considerably quicker than having two hands.

Ken: Just handling the watch, the jumping is so crisp it makes me want to keep turning the time.

Nicholas: The most fun is when you're QC-ing the watch and checking that it jumps consistently. You hear that camera shutter — whoosh. Because of how Christopher Ward developed the [JJ01] movement, it builds up power from 25 minutes prior, so it can go instantly. It's almost haptic. Wearing a Jump Hour without looking at it, you can feel the jump. It's an aide-memoire that another hour has passed.

Ken: From someone used to telling time with two hands, it's something unusual. With wandering hours, you can tell the wheels are turning, but with jump hour, it's the snap.

Nicholas: Exactly. I find it fascinating to see so many new jump hour watches coming out, which is fantastic. The more jump hour watches, the more people understand the complication. When we brought our first jump hour watch out, at our price point, there was nothing. Now, there are lots of really good options. That's great because it takes you back to the 1920s era.

Ken: I always say people ask if there are too many jump hours competing for the same thing. But it's about bringing awareness of this way of time-telling to everyone, making more people aware that there are alternative ways. That gets people interested in all jump hours everywhere. It's a rising tide that lifts all boats.

Nicholas: And the great thing is, once you change how you tell time on the watch, it opens up possibilities with design and dial. One thing that I think makes our Jump Hour distinctive is our use of negative space. Our designer, Lee [Yuen-Rapati], is absolutely a star at working out how to use it with the right proportions and decoration. If that watch had two hands, you wouldn't be able to have the same impact.

Arnos Design Story

Ken: I wanted to talk about the watch you're wearing, the Arnos, launched earlier this year. Talk about the design. I'm sure there were many decisions and trade-offs along the way. You also have the Archival 1930, also rectangular. Is this an evolution of that, or a new line?

Nicholas: When I restarted Fears, I had a choice about what the watches would be like. The obvious one would have been, "We've got this incredible archive of 130 years while Fears was running until the '70s, why don't we just recreate watches?" Especially in 2016, when vintage was so hot. But then you pigeonhole yourself as a heritage brand.

Fears is a British luxury watch company with heritage — there's a marked distinction.

For me, it's always been the idea of, if Fears hadn't closed in 1976, what would it be making today? We look at the archive and take inspiration, but we're not beholden to it. For our 175th anniversary in 2021, I decided to break my own rule. We made a watch that directly links to one in the archive. The Archival 1930, a recreation of a rectangular watch Fears made in 1930, was limited to 175 pieces. It used a new old stock movement; huge success. Very classic Art Deco styling.

I was always keen to have a rectangular piece in the collection. I love rectangular watches. There's something so elegant about them. For anyone who's not worn a rectangular watch, it's much more logical on the wrist, the shape, the way it goes around the wrist.

We'd decided to bring it back. We wanted to move from new old stock vintage movements to modern-day automatics. We wanted to make adjustments to the case but keep the same elegant, tall, slim proportions and curved case. When it came to the dial and design, that was different. I found myself in a problem that we were coming up with designs that were good, but not exceptional. What the world does not need is any more watches.

Ken: It's true. We have our phones. This is an art piece.

Nicholas: If you're going to create art, it's got to be exceptional. I kept saying, "No, this isn't right." Then one Saturday, I was about to go to bed, and I got this brainwave, this flash. I messaged Lee immediately and said, "Blue circle, grey rectangle." That's it. That was his brief.

Usually, when we're designing a watch, we have 40 to 50 different iterations and refinements. We didn't with this. Within a few weeks, he showed me the first mock-up. It's the only time in nine years working at Fears that I got tears in my eyes. It was one of those moments where I'm like, "This is so perfect."

We made a handful of tweaks, but it's probably the watch we've designed the least, yet I think it's the most refined, pure iteration of the Fears design language.

The Arnos is incredibly special because when you look at it, you'd naturally assume it's had months of design tweaks. It didn't. It was one of the easiest watches to design because of how Lee and I work together — we have a symbiotic relationship in how we think about and appreciate things. This watch was almost designed without words. Just a concept, and he nailed it.

Design Language & Philosophy

Ken: How would you describe the Fears design language?

Nicholas: Classical, very refined. Quite sophisticated, but in no way exclusive in a way that makes you feel you can't wear it and be part of it. Nothing is sadder than people who absolutely love a watch, and then get the watch but never feel like the owner. They feel like the watch owns them.

The watches we create have this level of refinement, sophistication and elegance. But even if you may not identify with those traits yourself, you don't feel intimidated by them. When you put a Fears on, it should make you feel like the best version of yourself, not a different person.

Ken: Design language is such a challenging thing. Another way to put it is, if you remove the logo, can you tell this is a watch from the brand? It's so difficult to find consistency and still be able to do what you want across different models.

Nicholas: Before I restarted Fears, I spent five years as an apprentice watchmaker at Rolex. People often say, "What a great beginning." But I was in the workshop, not the head office, making strategic decisions. But I took away two things from Rolex. One: It's a fiercely independent company, but actually quite humble. And they ignore what's going on in the rest of the industry. That has led to their huge success. That's something I try to emulate. We don't follow trends. If there's a trend, we try to ignore it.

It's important to me that any Fears we make today — when you look at it in 50 or 100 years — doesn't feel like a particular era. The other thing is, take any Rolex, take the name off the dial — you know it's Rolex. Certain brands I really admire, like Laurent Ferrier and FP Journe, have a design language that is so strong but has so much flexibility across different models.

But people already have an idea of what a Fears watch will be — certain proportions, certain elegance, certain refinement to the design. We don't pigeonhole ourselves. When you look at the Fears collection today, it's actually quite broad. We've taken the name, those five letters, and everything they stand for, and pulled it in lots of different ways.

Organisational Growth & Structure

Ken: We were chatting about your company and organisation; I'm impressed by how you think about your vision. You definitely have a plan, and you're very considered in what you do. Talk about how the brand has evolved in the past nine years and how you see it going forward.

Nicholas: On launch day in November 2016, people said, "So what's happening next?" It was that moment when I thought, "I know I've got a business plan, but I don't know what's coming next year." I look back and realise I was so wet behind the ears, so naive. You need that naivety, or you would never do it.

If I knew then what I know now, I don't think I would have had the courage.

As the company evolves, we're now a team of around 10 people. You're responsible for 10 people's mortgages, rents and livelihoods. With that comes great responsibility. Even though I own Fears, I restarted it, I view it as — I'm the current custodian. I have my tenure as managing director. I'm the fourth managing director. The previous three were my relatives. But there will be a fifth, a sixth. It's about thinking of the company in the long term.

That means putting in structure. Deliberately putting in checks and balances so I'm not the crazy emperor in an ivory tower. You've got to find that balance — you've got people, hardworking team members and colleagues — they've got to be able to come to work and enjoy working in a good environment.

For a small company, we almost have an over-engineered structure, hierarchy, the way we operate, departments and meetings. But that's very important because when you're making things like this, this isn't a hobby. This has never been a hobby for me. It's very important to treat it with respect.

Ken: Do you feel it's too early to have that kind of structure given the size you are?

Nicholas: When I talk to other business owners, they fall into camps. They either think it's brilliant, or they think it's so much bureaucracy and a waste of time. The bureaucracy makes it easier. You have structure. If you know the laws of the land, you know how to work within them. If everything's in a grey area, you waste so much time working out what you should be doing.

It could be seen as overkill, but I think it's actually a huge competitive advantage. As we continue to grow, the growth is relatively easy from a structural standpoint. Most companies go through huge teething problems. I always describe a company growing as like a teenager — very hormonal. But for us, it's easier.

Ken: That's very interesting. I've heard that the business structure you set up, going from starting to $1 million revenue, is very different from what you need going from one to five and five to 10. But it sounds like you've laid down the groundwork for bringing the brand from where it is today to where it needs to be in 15 years.

Nicholas: Back in the 1920s, Fears employed 100 watchmakers in Bristol. Fears was the largest watch company in the West of England. It was exported to 95 countries around the world. Actually, Fears should and can re-establish itself, but with all the ethics and morals and way of operating that is currently part of our vision.

Team Building & Leadership Philosophy

Ken: You definitely have a vision for what you want to achieve and a roadmap for how you're going to get there. I've seen the team you work with, and you talk about Lee as a designer — I can see you guys are just starting out. There's a lot to be excited about.

Nicholas: What's great to see is that my colleagues are very passionate about working at Fears and what they do. It's strange because they're not the ones who've restarted this. It's not their family's legacy, but people can see how everything we've achieved is because of them and just my gentle steering. It's because of the work they do, and that's really important to acknowledge.

Ken: I always tell my team: If you have passion, if you have pride in what you do, people can feel it. People believe in it even more if you believe in yourself. Through our conversation, I can feel the passion and pride you have for what you've built and want to achieve. Looking at your team and talking to them, I can feel that same energy. It's not easy to get to this level where everyone is on the same boat, on the same journey with you.

Nicholas: Running a business, certainly running a watch company, it's not easy, but it's incredibly rewarding. I've been into watches since I was a kid. Before I was a teenager. The fact that I get to create watches every day, I wake up knowing I basically have the best job in the world.

Closing Thoughts

What stands out most about Nicholas' approach is his conviction that he is simply the brand’s caretaker rather than its owner. Even after reviving Fears from decades of inactivity, he sees himself as one link in a much longer chain, fully aware that a fifth and sixth managing director will one day follow. This sense of stewardship has shaped every decision, from over-engineering the company structure — seen by some as visionary and by others as overly cautious — to prioritising resilience over short-term gains.

When he recalls the moment Lee shared the first Arnos concept — a deceptively simple design that nonetheless moved him to tears — it reveals the deeper motivation behind his work: the joy of seeing a clear idea brought to life with absolute fidelity. It’s a reminder that in watchmaking, true luxury often lies in the honest collaboration between designer and craftsman, rather than endless rounds of refinement.

Perhaps most importantly, Nicholas' ambition to model “good capitalism” feels like a quiet challenge to the norms of the industry. His readiness to protect supplier partnerships at the cost of profit margins, his commitment to employee development, and his insistence that moral responsibility must sit alongside commercial success all point to a different way of doing business. In a world where heritage is too often reduced to marketing, Fears shows how genuine family legacy, coupled with modern principles, can create something lasting, both in substance and in spirit.

You can learn more about Fears by clicking here.

*Responses have been slightly edited for length and clarity.

![Anthracite Hook Strap [kollokium x Delugs]](http://delugs.com/cdn/shop/files/20250919-A7405309_298x298_crop_center.jpg?v=1761299094)

![Anthracite Hook Strap [kollokium x Delugs]](http://delugs.com/cdn/shop/files/Kollokium_straps_Anthracite_1_298x298_crop_center.jpg?v=1761299094)

Buy One, Get One 15% Off

Buy One, Get One 15% Off

![Baby Blue CTS Rubber Strap for IWC Ingenieur [Prototype]](http://delugs.com/cdn/shop/files/20251001-DSC02482_1_298x298_crop_center.jpg?v=1759730616)

![Baby Blue CTS Rubber Strap for IWC Ingenieur [Prototype]](http://delugs.com/cdn/shop/files/IWC_Ingenieur_Rubber_CTS_Baby_Blue_298x298_crop_center.jpg?v=1759303635)